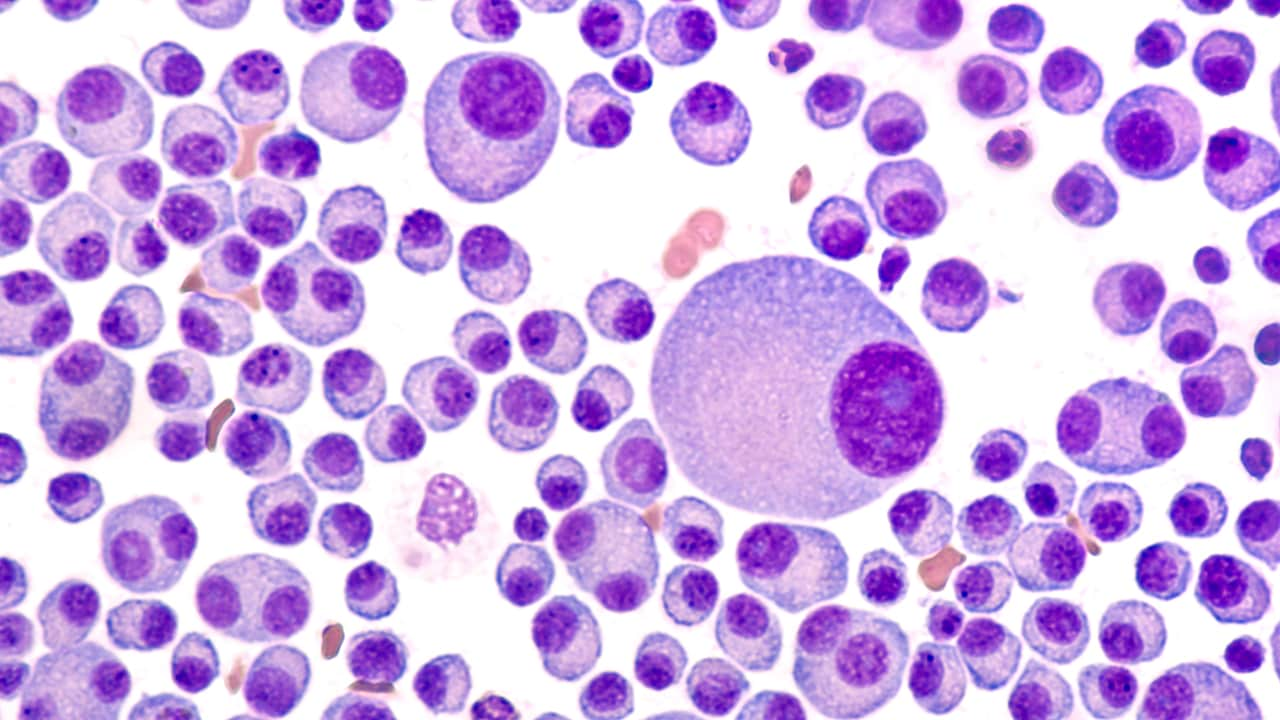

December 12, 2011 — Thalidomide (Thalomid, Celgene) and lenalidomide (Revlimid, Celgene) have proven highly effective in the treatment of multiple myeloma, but how they work in this disease has been a mystery. Now research that is unraveling the mechanism of their action might lead to a way to predict which patients will respond to this approach to therapy.

This research centers around a recently discovered protein, cereblon, which was reported to be responsible for the birth defects caused by thalidomide in a landmark paper published last year (Science. 2010;327:1345-1350).

That discovery prompted researchers at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Arizona, to investigate cereblon in multiple myeloma, and they now report that the protein is involved in the action that these drug have on this disease. In fact, the researchers suggest that thalidomide and lenalidomide, previously known as immunomodulatory drugs, should be renamed cereblon-binding small molecules to more accurately reflect their mechanism of action.

The research on cereblon in multiple myeloma was presented here at the American Society of Hematology 53rd Annual Meeting, and was highlighted at a press conference.

Dr. Keith Stewart

The work was summarized by senior author Keith Stewart, MD, professor of medicine in the division of hematology/oncology at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale.

Some of the work, conducted in multiple myeloma cell lines, showed that cereblon is essential for the activity of thalidomide and lenalidomide. Further study showed that lowering the level of cereblon in these cells lines allowed the drugs to work more efficiently, which suggests that high levels of cereblon are responsible for resistance to these agents.

In addition to the work in cell lines, the team analyzed DNA from multiple myeloma patients, using quantitative polymerase chain reaction. In 8 of 10 patients who were resistant to lenalidomide therapy, cereblon expression was significantly reduced (to 20% to 80% of baseline levels) at the time of drug resistance, which suggests that cereblon expression could be a biomarker for response to these drugs.

"Interestingly, some resistant patients had normal cereblon levels, suggesting that while cereblon may be an absolute requirement for response, there are likely other mechanisms that play a role in drug resistance," Dr. Stewart said. "These findings help us understand which patients may be more or less likely to respond to therapy and allow us to focus on other ways we can target cereblon as a possible biomarker to improve treatment and patient outcomes in multiple myeloma."

Thalidomide and lenalidomide work in about one third of patients with relapsed multiple myeloma, although the proportion who respond is higher when patients are treated after diagnosis. When asked if cereblon could be used to identify which patients would be likely to respond to these drugs, Dr. Stewart answered: "Not yet, but we are working on it."

"This work also suggests that we can begin to dissect out the cause of birth defects from the anticancer properties and develop safer drugs in the future," Dr. Stewart said.

These points were picked up by Jane Winter, MD, professor of medicine in the division of hematology/oncology at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, Illinois, who moderated the press conference. "The new insight into how these drugs work in multiple myeloma increases our understanding of how patients develop resistance to these drugs, and also lays the groundwork for the development of new therapies," she said.

Completely New

Commenting on the study for Medscape Medical News, David Siegel, MD, PhD, chief of multiple myeloma at the John Theurer Cancer Center, Hackensack University Medical Center, New Jersey, said that the finding of cereblon was something completely new.

Previously, attention was focused on the action of these drugs as tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors, he explained. This was the activity that appeared to be important in the treatment of leprosy, which is the use that led to the rehabilitation of thalidomide after it was removed from the market because it caused birth defects when taken by pregnant women during the 1950s and 1960s.

The benefit in multiple myeloma patients was only discovered in 1997 — quite serendipitously — because of the very determined wife of a young multiple myeloma patient, Dr. Siegel explained. She was pursuing all avenues for a treatment, and was initially pointed toward thalidomide because of its antiangiogenic properties. Unfortunately, thalidomide did not help her husband, but it worked in the next patient with multiple myeloma, and that finding spawned a whole new drug-development business. Celgene, the company that rehabilitated thalidomide, later developed the second-generation drug lenalidomide and is now developing a third-generation agent, pomalidomide.

Thalidomide and lenalidomide now generate annual sales of around $3 billion, Dr. Stewart noted at the press briefing.

American Society of Hematology (ASH) 53rd Annual Meeting: Abstract 127. Presented December 11, 2011.

Medscape Medical News © 2011 WebMD, LLC

Send comments and news tips to news@medscape.net.

Cite this: New Insight Into Drug Action in Multiple Myeloma - Medscape - Dec 12, 2011.

Comments